Synopsis:

Synopsis:

“Two Truths and a Lie” was a game the girls — Vivian, Natalie, Allison, and first-time camper Emma Davis, the youngest of the group — played all the time in their tiny cabin at Camp Nightingale fifteen years ago. But the games ended when Emma sleepily watched the others sneak out of the cabin in the middle of the night. Vivian pulled the cabin door shut, hushing Emma with a finger pressed to her lips and tell her she was too young. That was the last time Emma — or anyone else — saw the three older girls.

Emma is now an up-and-coming artist in New York City. Her paintings are massive canvases filled with dark leaves and gnarled branches. No one knows that every painting begins with three ghostly shapes in white dresses which lie beneath those images. Emma’s paintings come to the attention of Francesca Harris-White — Frannie — the wealthy socialite owner of Camp Nightingale. The camp was closed following the girls’ disappearance, but now Francesca implores Emma to return to the newly reopened camp, along with other former campers, as a painting instructor. By all indications, Frannie holds no grudge against Emma for what happened on that night long ago. Emma seizes the opportunity to make peace with the past and learn, at long last, what happened to her friends.

As soon as Emma arrives, it’s clear that all is not right at Camp Nightingale. Seemingly innocuous incidents set Emma on edge. Then she finds a security camera pointed directly at her cabin, and must deal with Frannie’s increasing distrust. Most disturbing of all, Emma discovers cryptic clues left behind by Vivian suggesting that the camp’s had unsavory origins. As she digs deeper, Emma finds herself sorting through lies from the past and facing present threats. The closer she gets to the truth about Camp Nightingale and its operators, the more she realizes that knowledge may come at a deadly price.

Review:

For Emma, her experiences at Camp Nightingale did not turn out to be part of her youth that she would remember fondly as she got older. Memories of roasting marshmallows, singing around a campfire, and making lifelong friends were not to be. Instead, Emma’s brief time there ended on the morning she awoke to find that her three roommates never returned from their nighttime excursion. Since that morning fifteen years ago, Emma has been haunted by not only their inexplicable disappearance and her resultant sorrow, but the role she may have played in it. Emma’s return to her life following the tragedy at Camp Nightingale was not without complications. But she eventually forged a career from, in part, the tragedy. Upon every blank canvas she places three small figures wearing white dresses before hiding them under layers of paint depicting tangled vines and dark woods. Only she knows that Vivian, Natalie, and Allison are entombed there.

When Frannie announces that she is reopening Camp Nightingale and asks Emma to return as an instructor, Emma is hesitant to accept, telling Frannie, “I’m not sure I can go back there again. Not after what happened.” But Frannie pushes her, suggesting that’s “precisely why you should go back.” Emma comes to see the invitation as an opportunity to reconcile the past by learning exactly what happened to her friends. She believes Frannie when she insists that she harbors no ill will toward Emma as a result of what happened — and the consequences, including quickly and quietly settled lawsuits filed by the girls’ grieving families. But Emma is no more prepared for the events she encounters at Camp Nightingale the second time than she was as a teenager.

What none of them understand is that the point of the game isn’t to fool others with a lie. The goal is to trick them by telling the truth.

Emma was younger than the other girls in her cabin because she arrived late and cabin assignments had already been made. Unlike the other campers, for whom Camp Nightingale was “the summer camp if you lived in Manhattan and had a bit of money,” Emma did not come from a wealthy, privileged background. She and her friends called it “Camp Rich Bitch,” but for just one summer her parents could afford to send her there. Natalie was the daughter of New York’s top orthopedic surgeon and Vivian’s mother was a celebrated Broadway actress. But it was Vivian who took Emma under her wing and was the leader in the group. The daughter of a senator, her older sister had drowned when, mistakenly believing the Central Park reservoir was frozen solid, she attempted to traverse it and fell through the broken ice. Emma looked up to and emulated the sophisticated Vivian, even as she found some of Vivian’s behavior startling. Vivian explained: “Everything is a game, Em. Whether you know it or not. Which means that sometimes a lie is more than just a lie. Sometimes it’s the only way to win.”

Incidents begin occurring that are, to Emma, suspicious, but are also susceptible of rationale explanation. Still, the discovery of the surveillance camera rattles her, especially when she learns that her hostess knows more about Emma’s past than she let on. Emma is tenacious and committed to learning her friends’ fate. But her quest for answers leads her on an increasingly dangerous foray into the past — the secrets Vivian was keeping, the true extent of the fall-out from the girls’ disappearance, and its impact upon not just Frannie and Emmy, but also upon Frannie’s adopted sons, Theo and Chet.

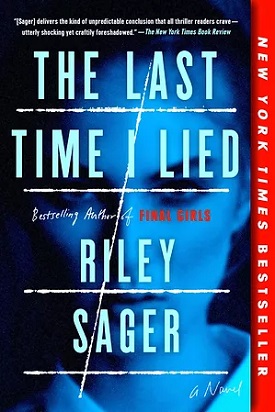

Author Riley Sager pulls readers into a beautiful setting that is full of secrets, resentments, and danger. Camp Nightingale, an otherwise idyllic backdrop, is as much a character in The Last Time I Lied as any of the story’s human inhabitants. Emma is a sympathetic character who has spent fifteen years trying to come to terms with an enormous tragedy and her perception of her role in it. Traumatized by the disappearance of her friends, Emma has suffered emotionally but, like a true artist, channeled her pain into her paintings. Emma is also, because of those factors, an inherently unreliable narrator. Now, however, she is ready to learn and face the truth. Did she have something to do with the girls’ disappearance? What act did she commit that was so horrible she has maintained her secrecy in the ensuing years? Every other character in the book is also a suspect.

The Last Time I Lied is fast-paced and intriguing. Like the pieces of paper the girls drop as they hike into the woods, designed to provide a trail back the way they came, Sager drops clues to the mystery at deftly-timed intervals, making it impossible to stop reading. The dramatic tension mounts as does the danger in which Emma, and her young charges, find themselves, leading to a pulse-pounding final confrontation. And a jaw-dropping conclusion. The Last Time I Lied is, by design, an ideal summer read. At camp, perhaps?

Excerpt from The Last Time I Lied

1

I paint the girls in the same order.

Vivian first.

Then Natalie.

Allison is last, even though she was first to leave the cabin and therefore technically the first to disappear.

My paintings are typically large. Massive, really. As big as a barn door, Randall likes to say. Yet the girls are always small. Inconsequential marks on a canvas that’s alarmingly wide.

Their arrival heralds the second stage of a painting, after I’ve laid down a background of earth and sky in hues with appropriately dark names. Spider black. Shadow gray. Blood red.

And midnight blue, of course. In my paintings, there’s always a bit of midnight.

Then come the girls, sometimes clustered together, sometimes scattered to far-flung corners of the canvas. I put them in white dresses that flare at the hems, as if they’re running from something. They’re usually turned so all that can be seen of them is their hair trailing behind them as they flee. On the rare occasions when I do paint a glimpse of their faces, it’s only the slimmest of profiles, nothing more than a single curved brushstroke.

I create the woods last, using a putty knife to slather paint onto the canvas in wide, unwieldy strokes. This process can take days, even weeks, me slightly dizzy from fumes as I glob on more paint, layer upon layer, keeping it thick.

I’ve heard Randall boast to potential buyers that my surfaces are like Van Gogh’s, with paint cresting as high as an inch off the canvas. I prefer to think I paint like nature, where true smoothness is a myth, especially in the woods. The chipped ridges of tree bark. The speckle of moss on rock. Several autumns’ worth of leaves coating the ground. That’s the nature I try to capture with my scrapes and bumps and whorls of paint.

So I add more and more, each wall-size canvas slowly succumbing to the forest of my imagination. Thick. Forbidding. Crowded with danger. The trees loom, dark and menacing. Vines don’t creep so much as coil, their loops tightening into choke holds. Underbrush covers the forest floor. Leaves blot out the sky.

I paint until there’s not a bare patch left on the canvas and the girls have been consumed by the forest, buried among the trees and vines and leaves, rendered invisible. Only then do I know a painting is finished, using the tip of a brush handle to swirl my name into the lower right-hand corner.

Emma Davis.

That same name, in that same borderline-illegible script, now graces a wall of the gallery, greeting visitors as they pass through the hulking sliding doors of this former warehouse in the Meatpacking District. Every other wall is filled with paintings. My paintings. Twenty-seven of them.

My first gallery show.

Randall has gone all out for the opening party, turning the place into a sort of urban forest. There are rust-colored walls and birch trees cut from a forest in New Jersey arranged in tasteful clumps. Ethereal house music throbs discreetly in the background. The lighting suggests October even though it’s a week until St. Patrick’s Day and outside the streets are piled with dirty slush.

The gallery is packed, though. I’ll give Randall that. Collectors, critics, and lookyloos elbow for space in front of the canvases, champagne glasses in hand, reaching every so often for the mushroom-and-goat-cheese croquettes that float by. Already I’ve been introduced to dozens of people whose names I’ve instantly forgotten. People of importance. Important enough for Randall to whisper who they are in my ear as I shake their hands.

“From the Times,” he says of a woman dressed head to toe in shades of purple. Of a man in an impeccably tailored suit and bright red sneakers, he simply whispers, “Christie’s.”

“Very impressive work,” Mr. Christie’s says, giving me a crooked smile. “They’re so bold.”

There’s surprise in his voice, as if women are somehow incapable of boldness. Or maybe his surprise stems from the fact that, in person, I’m anything but bold. Compared with other outsize personalities in the art world, I’m positively demure. No all-purple ensemble or flashy footwear for me. Tonight’s little black dress and black pumps with a kitten heel are as fancy as I get. Most days I dress in the same combination of khakis and paint-specked T-shirts. My only jewelry is the silver charm bracelet always wrapped around my left wrist. Hanging from it are three charms-tiny birds made of brushed pewter.

I once told Randall I dress so plainly because I want my paintings to stand out and not the other way around. In truth, boldness in one’s personality and appearance seems futile to me.

Vivian was bold in every way.

It didn’t keep her from disappearing.

During these meet and greets, I smile as wide as instructed, accept compliments, coyly defer the inevitable questions about what I plan to do next.

Once Randall has exhausted his supply of strangers to introduce, I hang back from the crowd, willing myself not to check each painting for the telltale red sticker signaling it’s been sold. Instead, I nurse a glass of champagne in a corner, the branch of a recently deforested birch tapping against my shoulder as I look around the room for people I actually know. There are many, which makes me grateful, even though it’s strange seeing them together in the same place. High school friends mingling with coworkers from the ad agency, fellow painters standing next to relatives who took the train in from Connecticut.

All of them, save for a single cousin, are men.

That’s not entirely an accident.

I perk up once Marc arrives fashionably late, sporting a proud grin as he surveys the scene. Although he claims to loathe the art world, Marc fits in perfectly. Bearded with adorably mussed hair. A plaid sport coat thrown over his worn Mickey Mouse T-shirt. Red sneakers that make Mr. Christie’s do a disappointed double take. Passing through the crowd, Marc snags a glass of champagne and one of the croquettes, which he pops into his mouth and chews thoughtfully.

“The cheese saves it,” he informs me. “But those watery mushrooms are a major infraction.”

“I haven’t tried one yet,” I say. “Too nervous.”

Marc puts a hand on my shoulder, steadying me. Just like he used to do when we lived together during art school. Every person, especially artists, needs a calming influence. For me, that person is Marc Stewart. My voice of reason. My best friend. My probable husband if not for the fact that we both like men.

I’m drawn to the romantically unattainable. Again, not a coincidence.

“You’re allowed to enjoy this, you know,” he says.

“I know.”

“And you can be proud of yourself. There’s no need to feel guilty. Artists are supposed to be inspired by life experiences. That’s what creativity is all about.”

Marc’s talking about the girls, of course. Buried inside every painting. Other than me, only he knows about their existence. The only thing I haven’t told him is why, fifteen years later, I continue to make them vanish over and over.

That’s one thing he’s better off not knowing.

I never intended to paint this way. In art school, I was drawn to simplicity in both color and form. Andy Warhol’s soup cans. Jasper Johns’s flags. Piet Mondrian’s bold squares and rigid black lines. Then came an assignment to paint a portrait of someone I knew who had died.

I chose the girls.

I painted Vivian first, because she burned brightest in my memory. That blond hair right out of a shampoo ad. Those incongruously dark eyes that looked black in the right light. The pert nose sprayed with freckles brought out by the sun. I put her in a white dress with an elaborate Victorian collar fanning around her swanlike neck and gave her the same enigmatic smile she displayed on her way out of the cabin.

You’re too young for this, Em.

Natalie came next. High forehead. Square chin. Hair pulled tight in a ponytail. Her white dress got a dainty lace collar that downplayed her thick neck and broad shoulders.

Finally, there was Allison, with her wholesome look. Apple cheeks and slender nose. Brows two shades darker than her flaxen hair, so thin and perfect they looked like they had been drawn on with brown pencil. I painted an Elizabethan ruff around her neck, frilly and regal.

Yet there was something wrong with the finished painting. Something that gnawed at me until the night before the project was due, when I awoke at 2:00 a.m. and saw the three of them staring at me from across the room.

Seeing them. That was the problem.

I crept out of bed and approached the canvas. I grabbed a brush, dabbed it in some brown paint, and smeared a line over their eyes. A tree branch, blinding them. More branches followed. Then plants and vines and whole trees, all of them gliding off the brush onto the canvas, as if sprouting there. By dawn, most of the canvas had been besieged by forest. All that remained of Vivian, Natalie, and Allison were shreds of their white dresses, patches of skin, locks of hair.

That became No. 1. The first in my forest series. The only one where even a fraction of the girls is visible. That piece, which got the highest grade in the class after I explained its meaning to my instructor, is absent from the gallery show. It hangs in my loft, not for sale.

Most of the others are here, though, with each painting taking up a full wall of the multichambered gallery. Seeing them together like this, with their gnarled branches and vibrant leaves, makes me realize how obsessive the whole endeavor is. Knowing I’ve spent years painting the same subject unnerves me.

“I am proud,” I tell Marc before taking a sip of champagne.

He downs his glass in one gulp and grabs a fresh one. “Then what’s up? You seem vexed.”

He says it with a reedy British accent, a dead-on impersonation of Vincent Price in that campy horror movie neither of us can remember the name of. All we know is that we were stoned when we watched it on TV one night, and the line made us howl with laughter. We say it to each other far too often.

“It’s just weird. All of this.” I use my champagne flute to gesture at the paintings dominating the walls, the people lined up in front of them, Randall kissing both cheeks of a svelte European couple who just walked through the door. “I never expected any of this.”

I’m not being humble. It’s the truth. If I had expected a gallery show, I would have actually named my work. Instead, I simply numbered them in the order they were painted. No. 1 through No. 33.

Randall, the gallery, this surreal opening reception-all of it is a happy accident. The product of being in the right place at the right time. That right place, incidentally, was Marc’s bistro in the West Village. At the time, I was in my fourth year of being the in-house artist at an ad agency. It was neither enjoyable nor fulfilling, but it paid the rent on a crumbling loft big enough to fit my forest canvases. After an overhead pipe leaked into the bistro, Marc needed something to temporarily mask a wall’s worth of water damage. I loaned him No. 8 because it was the biggest and able to cover the most square footage.

That right time was a week later, when the owner of a small gallery a few blocks away popped into Marc’s place for lunch. He saw the painting, was suitably intrigued, and asked Marc about the artist.

That led to one of my paintings-No. 7-being displayed in the gallery. It sold within a week. The owner asked for more. I gave him three. One of the paintings-lucky No. 13-caught the eye of a young art lover who posted a picture of it on Instagram. That picture was noticed by her employer, a television actress known for setting trends. She bought the painting and hung it in her dining room, showing it off during a dinner party for a small group of friends. One of those friends, an editor at Vogue, told his cousin, the owner of a larger, more prestigious gallery. That cousin is Randall, who currently roams the gallery, coiling his arms around every guest he sees.

What none of them knows-not Randall, not the actress, not even Marc-is that those thirty-three canvases are the only things I’ve painted outside my duties at the ad agency. There are no fresh ideas percolating in this artist’s brain, no inspiration sparking me into productivity. I’ve attempted other things, of course, more from a nagging sense of responsibility than actual desire. But I’m never able to move beyond those initial, halfhearted efforts. I return to the girls every damn time.

I know I can’t keep painting them, losing them in the woods again and again. To that end, I’ve vowed not to paint another. There won’t be a No. 34 or a No. 46 or, God forbid, a No. 112.

That’s why I don’t answer when everyone asks me what I’m working on next. I have no answer to give. My future is quite literally a blank canvas, waiting for me to fill it. The only thing I’ve painted in the past six months is my studio, using a roller to convert it from daffodil yellow to robin’s-egg blue.

If there’s anything vexing me, it’s that. I’m a one-hit wonder. A bold lady painter whose life’s work is on these walls.

As a result, I feel helpless when Marc leaves my side to chat up a handsome cater waiter, giving Randall the perfect moment to clutch my wrist and drag me to a slender woman studying No. 30, my largest work to date. Although I can’t see the woman’s face, I know she’s important. Everyone else I’ve met tonight has been guided to me instead of the other way around.

“Here she is, darling,” Randall announces. “The artist herself.”

The woman whirls around, fixing me with a friendly, green-eyed gaze I haven’t seen in fifteen years. It’s a look you easily remember. The kind of gaze that, when aimed at you, makes you feel like the most important person in the world.

Comments are closed.