Synopsis:

Synopsis:

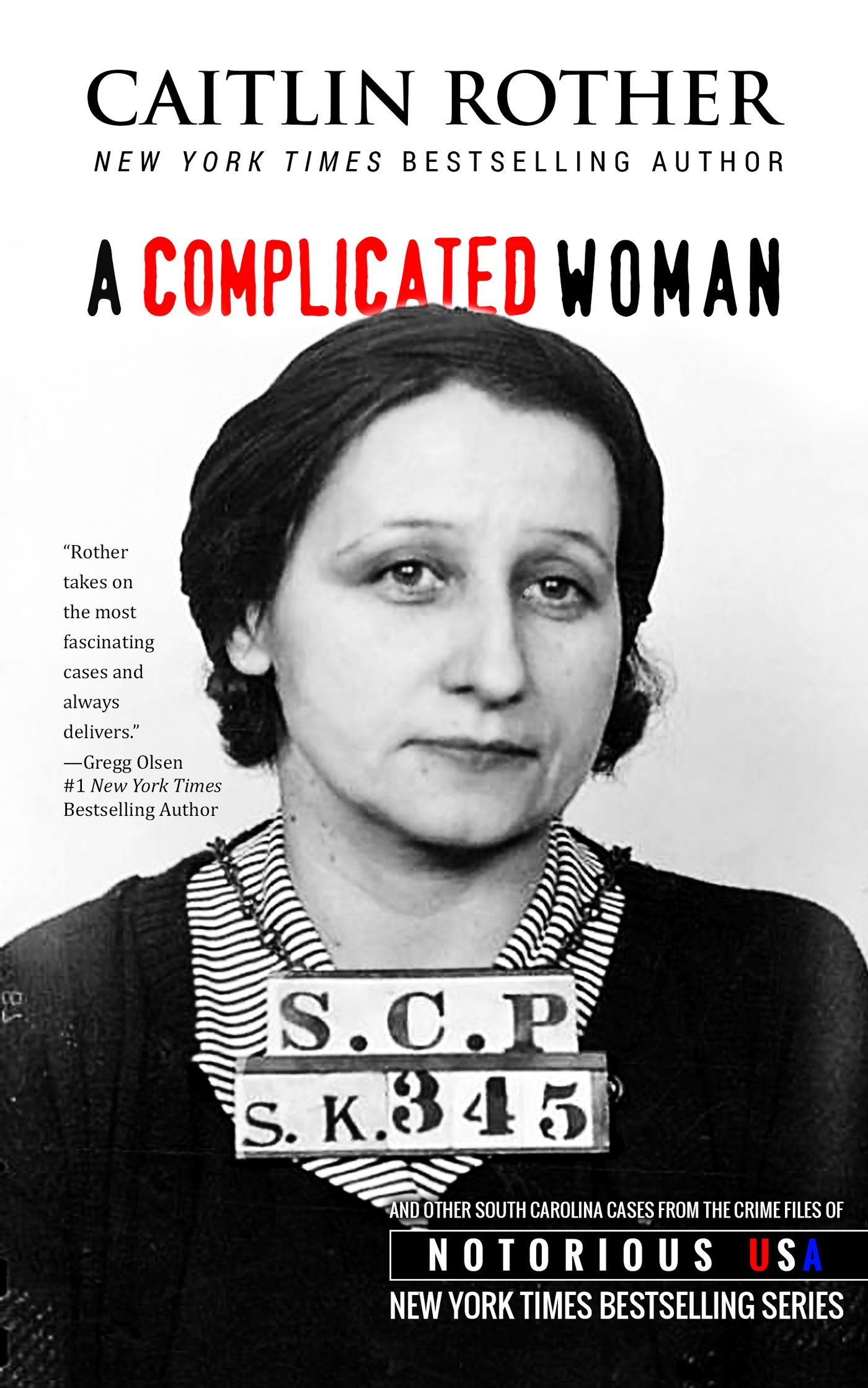

The first of three entries in Greg Olson’s “Notorious USA” series from best-selling true crime novelist Caitlin Rother, A Complicated Woman focuses upon three South Carolina murderers. Two were ultimately executed and one may yet be.

It may come as a surprise to readers to learn that South Carolina’s crime rate has exceeded the national average nearly every year since 1975. Despite the disparities in population, nearly 35 percent more murders take place in South Carolina than in either California or Texas, and in 1994, South Carolina housed more inmates per capita in its thirty-two prisons than any other state. Even after America’s crime statistics dropped dramatically, the violent crime rate in South Caroline remained 51 percent higher than the national average as of 2010.

Rother profiles the first woman ever executed in South Carolina. She died in the electric chair as a result of a long-running feud fueled by a dead calf. South Carolina’s most prolific serial killer was ultimately put to death after murdering a fellow death row inmate. And in 2015, a young white man sought to incite a race war, but instead inspired a national dialogue about race, violence, the lingering impact of historical events and perspectives, and, most importantly, forgiveness.

Review:

A Complicated Woman focuses on three killers and the crimes for which two of them paid with their lives while the fate of the third is as yet undetermined.

Rother compellingly recounts the story of Sue Stidham Logue, born in 1899 into a family familiar with taking lives, who married at the age of fifteen. Her story is more like a chapter from America’s Wild West than the mid-twentieth century. Romantically linked to both her brother-in-law and the legendary and scandalous U.S. Senator Strom Thurman, Logue’s lifelong connection to violence continued into her marriage.

By 1940, a long-running feud between the Logues and their neighbor, Davis Timmerman, reached critical proportions, with Logue publicly threatening to kill Timmerman. Just a month later, Timmerman’s mule kicked one of the Logues’ calves, injuring it so badly that it had to be euthanized. When Logue’s husband went to the collect the $20 settlement agreed upon, a confrontation ensued that left Logue’s husband dead and Timmerman charged with murder. After a jury believed Timmerman acted in self-defense, Logue entered into a conspiracy to ensure that her brand of justice was served. For that decision, she paid with her life but not before several more men died, including two law enforcement officials, and Thurmond himself ended up arresting her.

Like Logue, Donald “Pee Wee” Gaskins, Jr., born in 1933, learned about and was, in fact, turned on by violence early in life. Rother details his failed marriages and string of sadistic crimes. Gaskins entered into a plea deal to avoid the death penalty under the terms of which he was convicted of seven murders, but he was responsible for many more deaths and bragged about committing even more, although many of his claims were either debunked or not susceptible of confirmation. Ultimately, his participation in the race-based revenge killing of another inmate resulted in his 1992 execution after both the South Carolina and U.S. Supreme Courts refused to intervene. Rother explains that Gaskins’ place in history was secured by his status “as the first white man in the U.S. over the past fifty years, and the first in South Carolina in the past 111 years, to be executed for killing a black man. At the time, this racial pattern of executions represented only a tiny fraction — only two-tenths of one percent — of all executions nationally.” At the time, however, his execution was viewed “more as a deterrent against prison killings than anything else.’

Lastly, Rother explores the June 17, 2015, shooting of the “Charleston Nine,” nine African-Americans during a Bible study in a historic Charleston church. Dylann Storm Roof, a twenty-one-year-old white man, deliberately targeted the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church because of its history and symbolism — and to ensure that he killed only white people. Having been welcomed into the Bible study, Roof announced, “I’m here to shoot black people” as he started firing. As he left the building, he told a seventy-two-year-old woman he was not going to shoot her because “I’m going to leave you to tell the story.” As of September 2015, the state was seeking the death penalty against Roof, despite opposition from many of the victims’ family members. Solicitor Scarlett A. Wilson observed that “forgiveness does not necessarily mean foregoing consequences” and Roof’s crime calls for the “ultimate punishment.” Rother’s descriptions of Roof’s unspeakable crime and the manhunt that ensued, and examination of Roof’s upbringing and motivations comprise the most comprehensive of the three profiles included, as well as some of her most measured and, as a result, best writing to date.

Rother is recognized as an exhaustive, painstaking researcher of her topics and A Complicated Woman exemplifies that work ethic. Her presentation in historical order of the lives and crimes of three killers, set against the backdrop of the time periods in which they committed their crimes, is fascinating and thought-provoking. In true Rother style, A Complicated Woman evokes far more questions than it answers about the thought processes of those murderers, the progress and status of race relations in 2016 America, conditions of incarceration, and, of course, the efficacy of capital punishment.

A Complicated Woman is a Kindle short ebook in a series focusing upon crimes committed in each of the United States. Rother will follow this effort with volumes devoted to Georgia and Florida.

1 Comment

Pingback: Guest Post: And Now For Something A Little Different | Colloquium